|

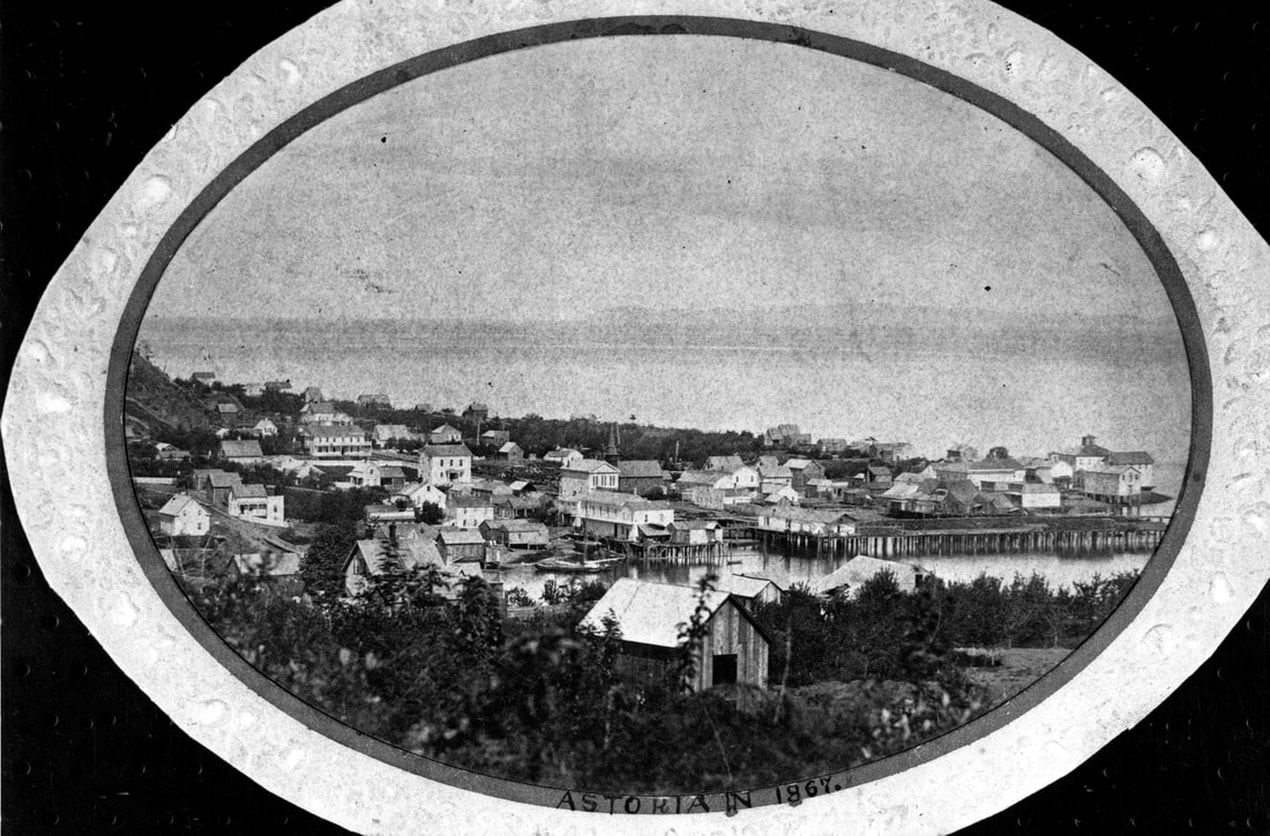

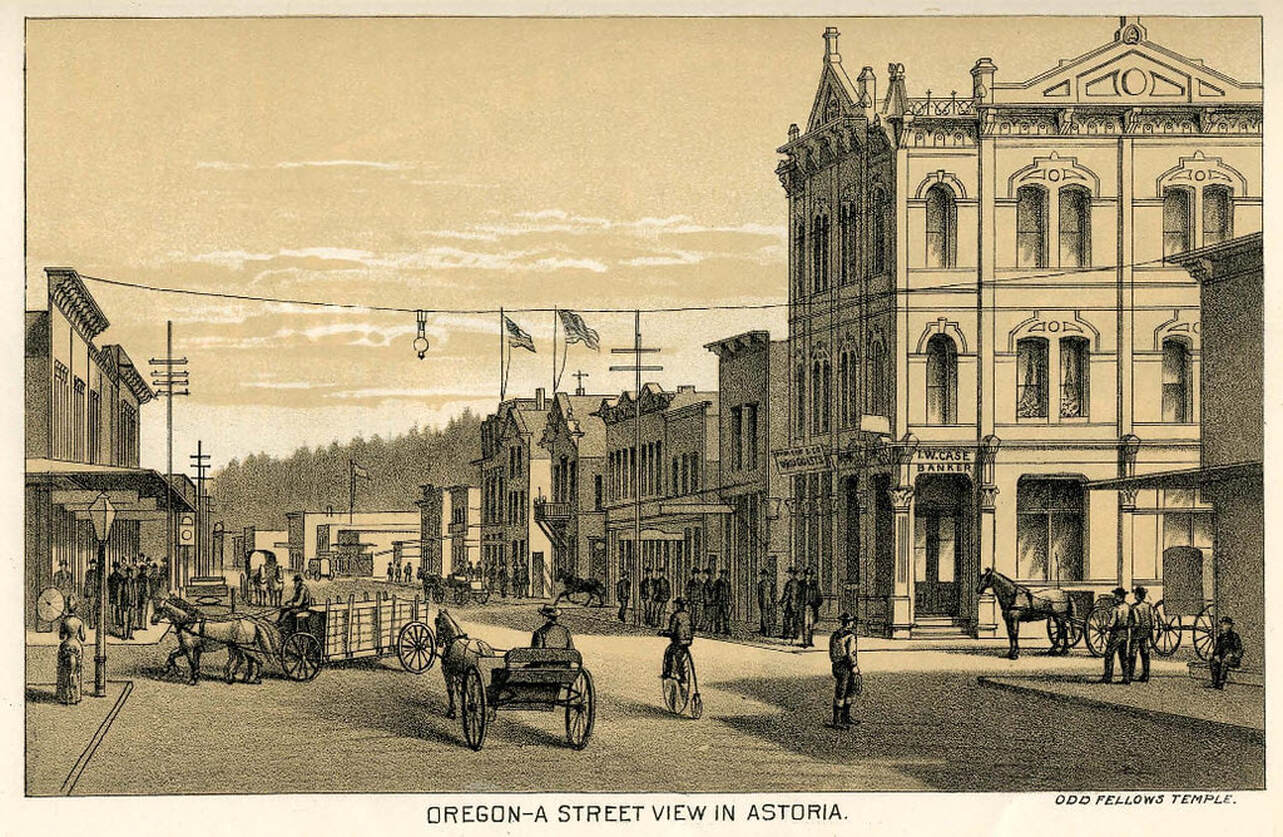

Astoria was built over the tide flats atop wood pilings and was able to develop a strong economy with help from its timber and salmon industries. This tour takes us back in time to Fort Astoria to the year 1811 and gives us a glimpse of Astoria throughout the nineteenth century. Try to picture in your mind horse-drawn vehicles clopping along wooden streets, mills and wharves built out over the water with the smell of fish and timber, rowdy saloons, bustling cigar and furniture shops, and boarding houses. Some of the houses that were built in the 1800s still stand today. |

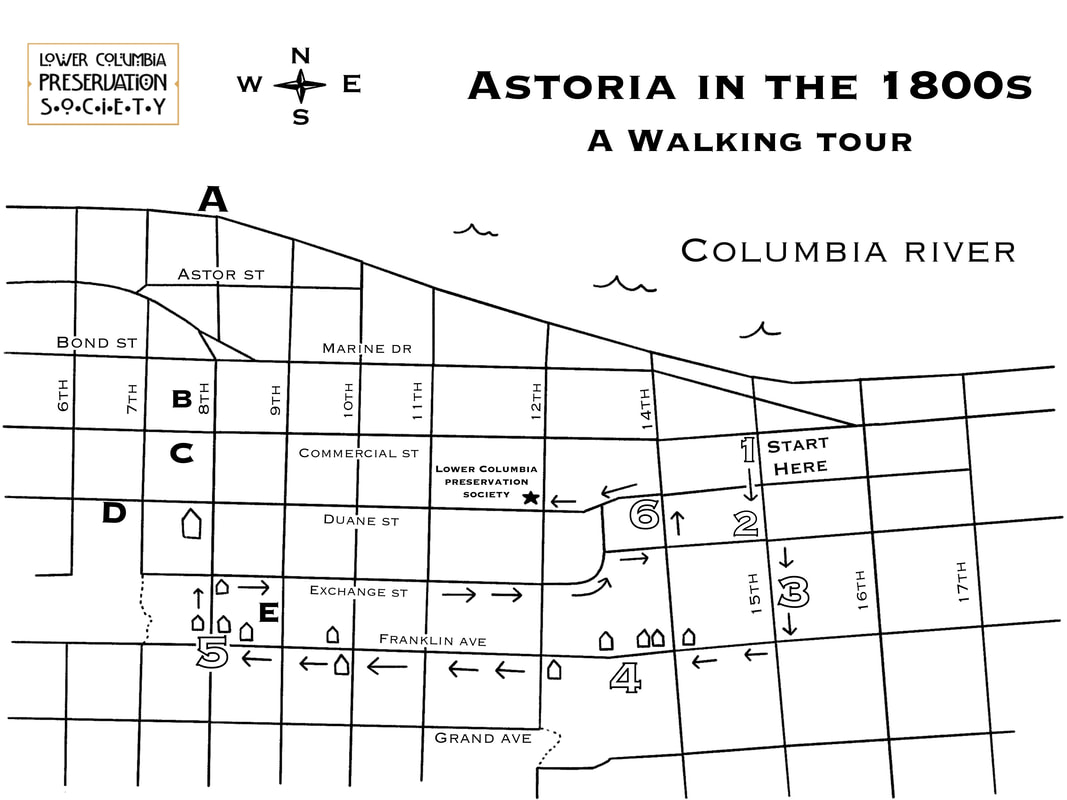

On the map, you will find seven numbered sites where we will stop and talk about the site’s history, and arrows that point the direction of our path.

Let’s begin.

Head over to Commercial Street at the corner of 15th. You will notice that the edge of the sidewalk on the south side of the street has a park down below. Let’s use our imaginations. If you will, grab hold of the sidewalk railing, and picture yourself on the deck of a rocking ship. You’ve just arrived to Astoria after a journey down the Columbia. Where shall we dock? If you peer over the edge and look down, you will see a large brown rock. This natural structure is more than just any old rock. As a ship captain in the early 1800s, this rock served as a beacon for you to determine whether or not it was a safe time to pull your ship in for dock.

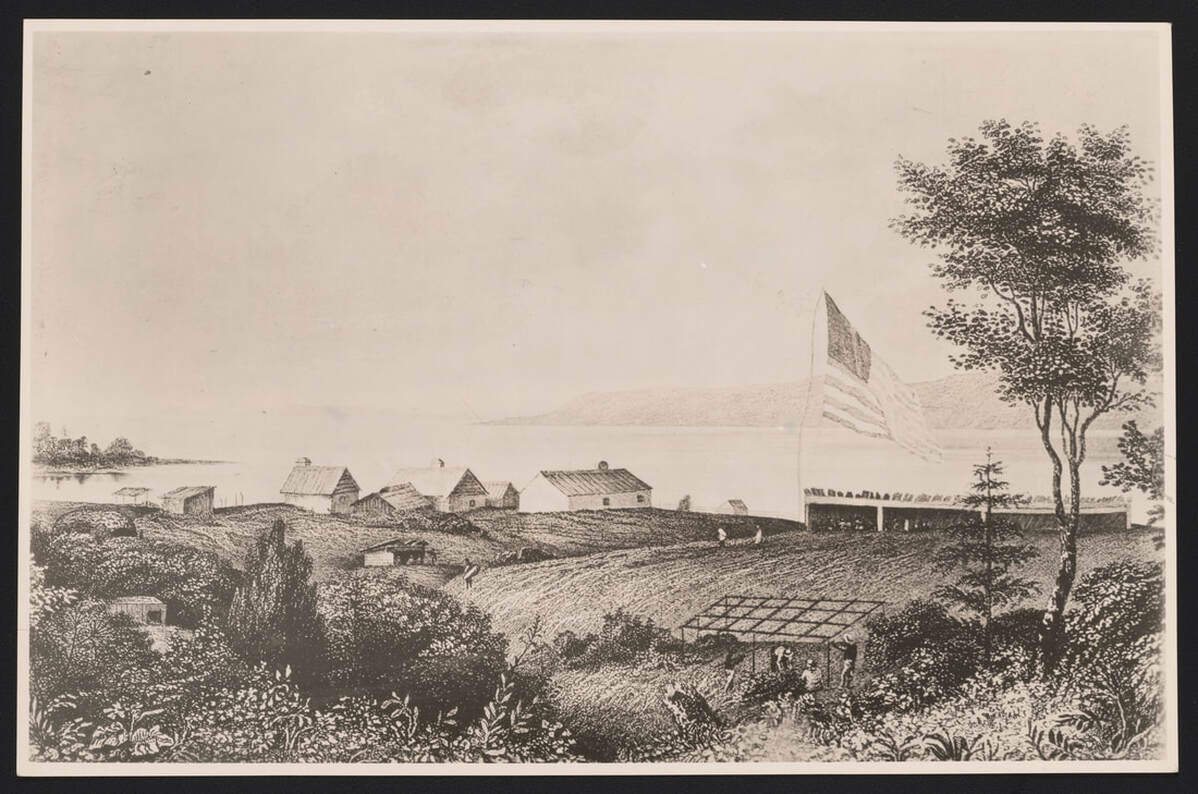

It was aptly named Tidal Rock…but what’s in a name? Columbia River is affected by tides and its water levels rise and fall. At times of low tide, when the water has ebbed back, Tidal Rock would appear above the water. Early Astorians carved lines into this rock to gauge exactly how high or low the water was at certain times in order to know if it was safe to bring a ship close in to dock. Astoria was originally built over the river. As you can see, our city sits on a craggy hill. When the Europeans arrived in 1811, the hillside was completely forested. Logging all of the trees and building into the steep ridge was intimidating. At that time, it made more sense to drive pilings into the muddy flats and build over the water. In 1811, your imaginary ship would certainly be floating at the river’s edge in the spot you’re standing now.

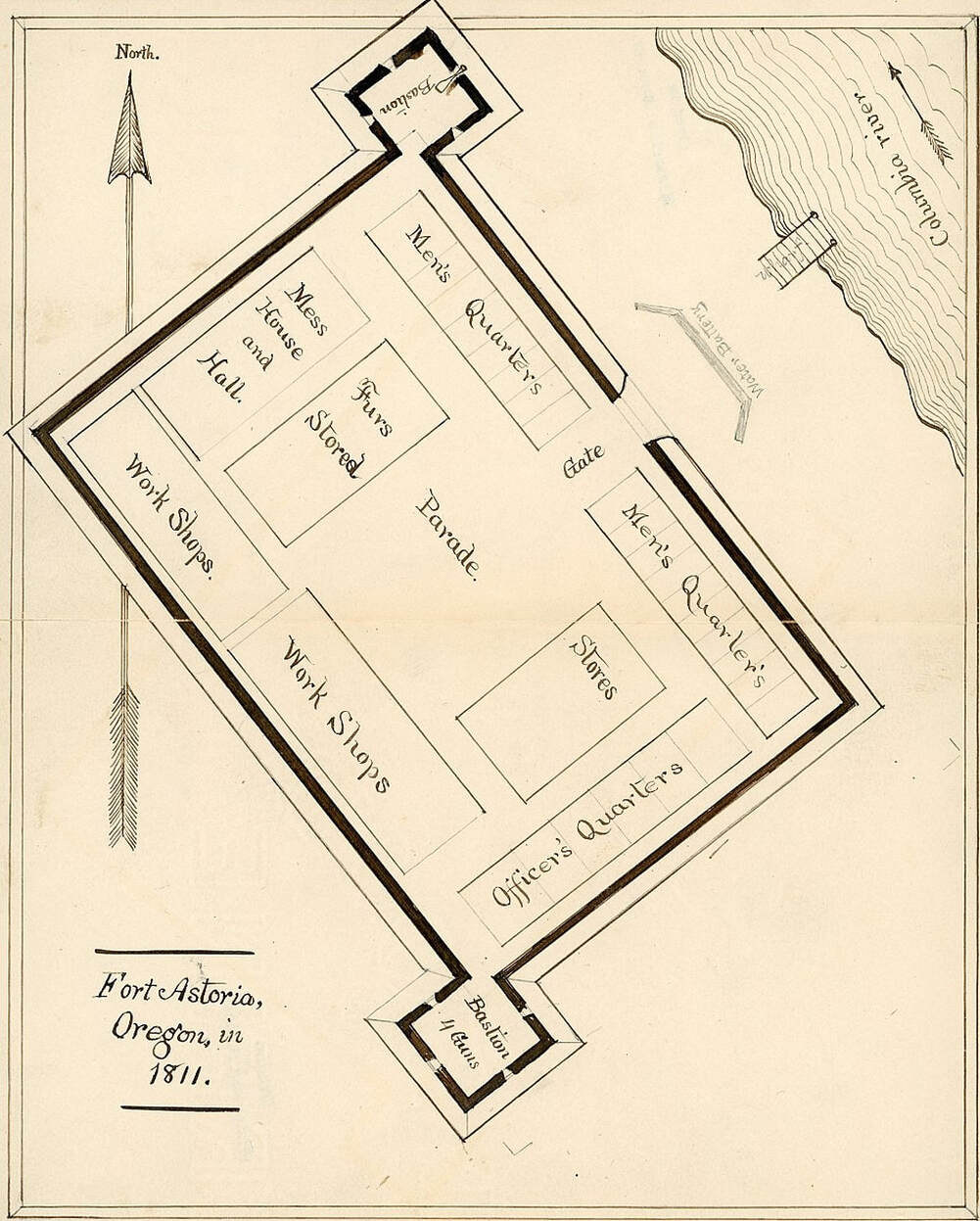

Okay, back to the story. It was 1810 when the American merchant ship, Tonquin, left New York with the Pacific Fur Company to start a fur trading post on the Pacific Coast. Pacific Fur Company was owned by the New York merchant John Jacob Astor, who incidentally, never visited Astoria. The Tonquin navigated around the southern most tip of South America, stopped over in Hawaii, then sailed into the mouth of the Columbia and made land here in mid-April of 1811. Let’s go see where the crew built their trading post. Go up 15th Street and stop when you reach Exchange. On your right you will see a small park with a replica of a fort in it. As soon as the Tonquin moored and its crew of proprietors, clerks, laborers, smiths, and a group of native Hawaiians who had joined them on their journey disembarked, everyday was work work work. At once, the land in this location was cleared and the trading post began construction.

From the journals of Alfred Seton, clerk aboard the Tonquin:

May 25th. Saturday. Disagreeable rainy weather. Wind S.W. People variously employed.

27th. Monday. Clear, dry weather. People variously employed. Erected a saw pit.

28th. Tuesday. Rainy weather. People employed as usual.

29th. Wednesday. Dry & pleasant weather. People variously employed. Mr. R. Stuart arrived with Cedar Bark.

May 30th. Thursday. Clear & pleasant weather. People employed as usual.

And so on.

In August, the crew began building the post:

8th. Thursday. Pleasant wea: Wind S.W. People employed as yesterday. Our hunter arrived overnight and informed us of his having killed a deer. Three Men in a canoe went off with him about 2 A.M. to fetch it, in which they did not succeed until 3 P.M. It had a good deal of tallow, & is the first fat one we have yet seen. In the afternoon, a party began to set up the Pickets. Matthews finished the lower story of the Bastion. Planked the swivels, etc. Sicklist as yesterday.

May 25th. Saturday. Disagreeable rainy weather. Wind S.W. People variously employed.

27th. Monday. Clear, dry weather. People variously employed. Erected a saw pit.

28th. Tuesday. Rainy weather. People employed as usual.

29th. Wednesday. Dry & pleasant weather. People variously employed. Mr. R. Stuart arrived with Cedar Bark.

May 30th. Thursday. Clear & pleasant weather. People employed as usual.

And so on.

In August, the crew began building the post:

8th. Thursday. Pleasant wea: Wind S.W. People employed as yesterday. Our hunter arrived overnight and informed us of his having killed a deer. Three Men in a canoe went off with him about 2 A.M. to fetch it, in which they did not succeed until 3 P.M. It had a good deal of tallow, & is the first fat one we have yet seen. In the afternoon, a party began to set up the Pickets. Matthews finished the lower story of the Bastion. Planked the swivels, etc. Sicklist as yesterday.

You can see this park has a replica of one of the bastions of the building with a wooden palisade. This structure was built in 1956. The mural on the back of the Fort George building depicts the remainder of the fort, the view of the Columbia River, and individuals from the Clatsop coastal tribe. It was painted by local artists, Roger McKay and Sally Lackaff. Much of the fur trading of beaver, otter, fox, and squirrel pelts was with the Clatsop and neighboring Chinook tribes with the intention to bring the furs back east. Notice on the streets and sidewalks, there are green lines. These depict the outline of the original fort.

In 1813, amid the British-American War of 1812, Pacific Fur Company were told that a British warship was on the way to seize their fort. In haste, they sold the company along with the fort and all of its assets to the British owned, Montreal-based North West Company in October and in December, the British eventually arrived.

Tonquin clerk, Gabriel Franchere recalls the arrival of the British ship, the Racoon, led by Captain Black:

“After dinner the captain had guns distributed to the employees of the company and we all gathered, thus armed, on a platform on which a flagstaff had been erected. There the captain took a British flag he had brought for the purpose and had it run up on the staff. Then, taking a bottle of Madeira wine, he broke it across the staff, declaring in a loud voice that he was taking possession fo the establishment in the name of His Royal Majesty. And he changed the name of the Fort from Astoria to Fort George.”

For decades, there was much competition over the Pacific Northwest by several territories. However, in 1846 Oregon officially belonged to the United States when the Oregon Treaty was signed. Oregon became the 33rd state of the U.S. on February 14th, 1859.

“After dinner the captain had guns distributed to the employees of the company and we all gathered, thus armed, on a platform on which a flagstaff had been erected. There the captain took a British flag he had brought for the purpose and had it run up on the staff. Then, taking a bottle of Madeira wine, he broke it across the staff, declaring in a loud voice that he was taking possession fo the establishment in the name of His Royal Majesty. And he changed the name of the Fort from Astoria to Fort George.”

For decades, there was much competition over the Pacific Northwest by several territories. However, in 1846 Oregon officially belonged to the United States when the Oregon Treaty was signed. Oregon became the 33rd state of the U.S. on February 14th, 1859.

|

Let’s hike up the hill about a half block. On the east side of 15th street, we will find another small park with an obelisk in the center. This is where Astoria’s first post office was built. What is especially interesting about the post office is that it was the first U.S. Post Office west of the Rocky Mountains. |

In 1843, a surveyor by the name of John M. Shively took out a donation land claim in Astoria. He called it “Shively’s Astoria.” Then in 1847, he decided that Astoria needed a post office. With support from Washington D.C., Shively and his wife moved into a two story home designating one of its rooms to the post office. President James K. Polk appointed Shively as postmaster. At that time, mail was delivered via ships along the Columbia River and it sometimes took months to send or receive letters. In 1869, a new post office was built in the location of our present day post office. Shively’s old home was torn down in 1906 and in 1955, this monument was put in its place. If you look closely at the monument on the ground, you will see a relief of the original building.

You will see the name Shively sprinkled around Astoria. Downtown Astoria was split between two land claims: John Shively and John McClure. Their claims meet between 12th and 14th streets. At 13th Street? No, in most of downtown, there is no 13th street. We’ll talk about that when we get there.

Take a right onto Franklin Ave. and behold as we step back in time. Many houses in this neighborhood have been well preserved with their original characteristics and appear similar to the year they were built. Notice on the map some little house shaped outlines. These mark several of the houses on these next few blocks that were constructed in the mid to late 1800s.

The first house is the right, 1410 Franklin:

Take a right onto Franklin Ave. and behold as we step back in time. Many houses in this neighborhood have been well preserved with their original characteristics and appear similar to the year they were built. Notice on the map some little house shaped outlines. These mark several of the houses on these next few blocks that were constructed in the mid to late 1800s.

The first house is the right, 1410 Franklin:

Beginning construction in 1866, this house took eleven years to complete. During the home’s early years, its stewards faced multiple tragedies. The house was originally built for George Warren and his wife Frances Stevens Warren. George was unfortunately killed in a logging accident before the house was finished. Four years later, Frances married I.W. Case and he moved into this house. As a businessman, Case was involved in banking and insurance. As a local politician, Case served as Astoria mayor and county treasurer. Sadly, Frances died from childbirth in 1882. Case, himself, died in 1895. His second wife used this home as a boarding house until it was sold to a new family in 1906.

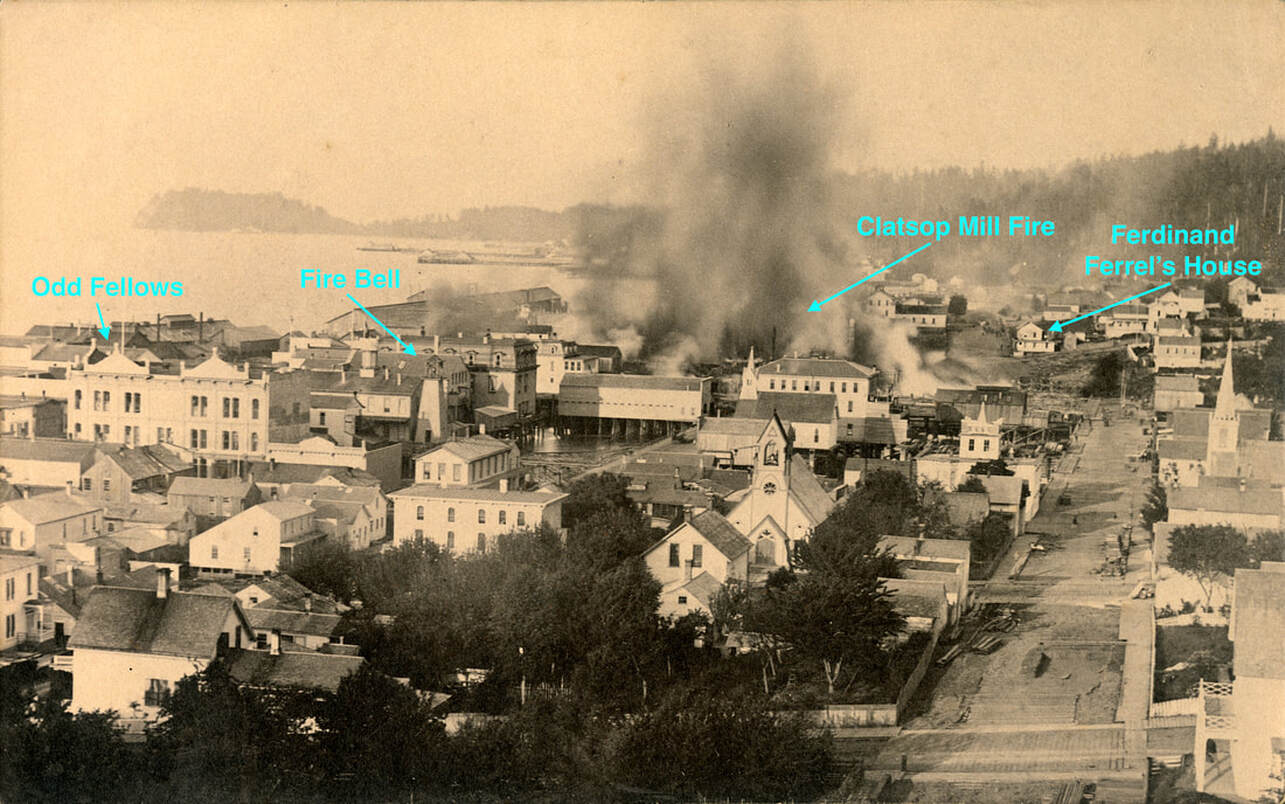

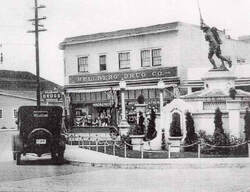

In this late 1800s image of Downtown Astoria, you can see the original Odd Fellows building. Because of its ornate roof, you will notice this building in the background of many pre 1922 fire photographs. Use that as a reference to figure out where buildings are in old photos and images in order to compare where things are today. The present day Odd Fellows building sits on foundation of the original Odd Fellows building. The intersection seen in this image is Commercial and 10th Streets. If you look carefully on the first floor of the Odd Fellows building, you'll see that a sign reads: I.W. Case banker. Many brotherhood buildings offered rentable office and merchant space on their ground floors to afford their big beautiful buildings. Take note of the horse drawn vehicles and the Penny Farthing bicycle presented in both this postcard and the photo of Frances Warren Steven's house.

Once you cross 14th, you will see 1388 Franklin Ave.

Charles Stevens came to Astoria in 1852 and built this house in 1867. He was a prominent writer and became city recorder and treasurer of the Clatsop chapter of the American Bible Association. In 1875, Charles and his son, Benjamin, opened a bookstore downtown called Charles Stevens & Sons City Bookstore. Charles and his wife, Ann Hopkinson, bore nine total children. One of his daughters was Frances Stevens from our previous house. Another daughter was Esther Stevens, who married Captain Hiram Brown who we will discuss shortly. During the 1880s, a kitchen and breakfast nook were built as additions to the house and sadly, Charles’ wife, Ann, died. While Charles was quite an accomplished man, he was best known for his poetry and letter writing. He died in 1900.

Charles Stevens came to Astoria in 1852 and built this house in 1867. He was a prominent writer and became city recorder and treasurer of the Clatsop chapter of the American Bible Association. In 1875, Charles and his son, Benjamin, opened a bookstore downtown called Charles Stevens & Sons City Bookstore. Charles and his wife, Ann Hopkinson, bore nine total children. One of his daughters was Frances Stevens from our previous house. Another daughter was Esther Stevens, who married Captain Hiram Brown who we will discuss shortly. During the 1880s, a kitchen and breakfast nook were built as additions to the house and sadly, Charles’ wife, Ann, died. While Charles was quite an accomplished man, he was best known for his poetry and letter writing. He died in 1900.

From Charles Stevens Letters:

“Astoria November 14th 1869

For myself I have been playing the carpenter for nearly a year back in building my house, and now have turned “stone mason,” by making a wall under it, it is such bad weather that I fear I will not be able to finish it this season, I am in no business to earn a living by, but as soon as I can finish my house, I will find some kind of employment or climb a tree…”

“Astoria November 14th 1869

For myself I have been playing the carpenter for nearly a year back in building my house, and now have turned “stone mason,” by making a wall under it, it is such bad weather that I fear I will not be able to finish it this season, I am in no business to earn a living by, but as soon as I can finish my house, I will find some kind of employment or climb a tree…”

1370 Franklin Ave.

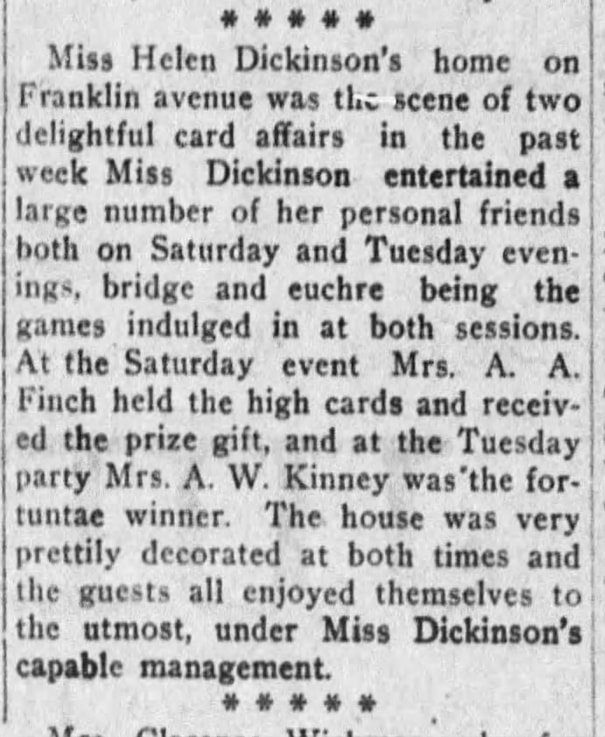

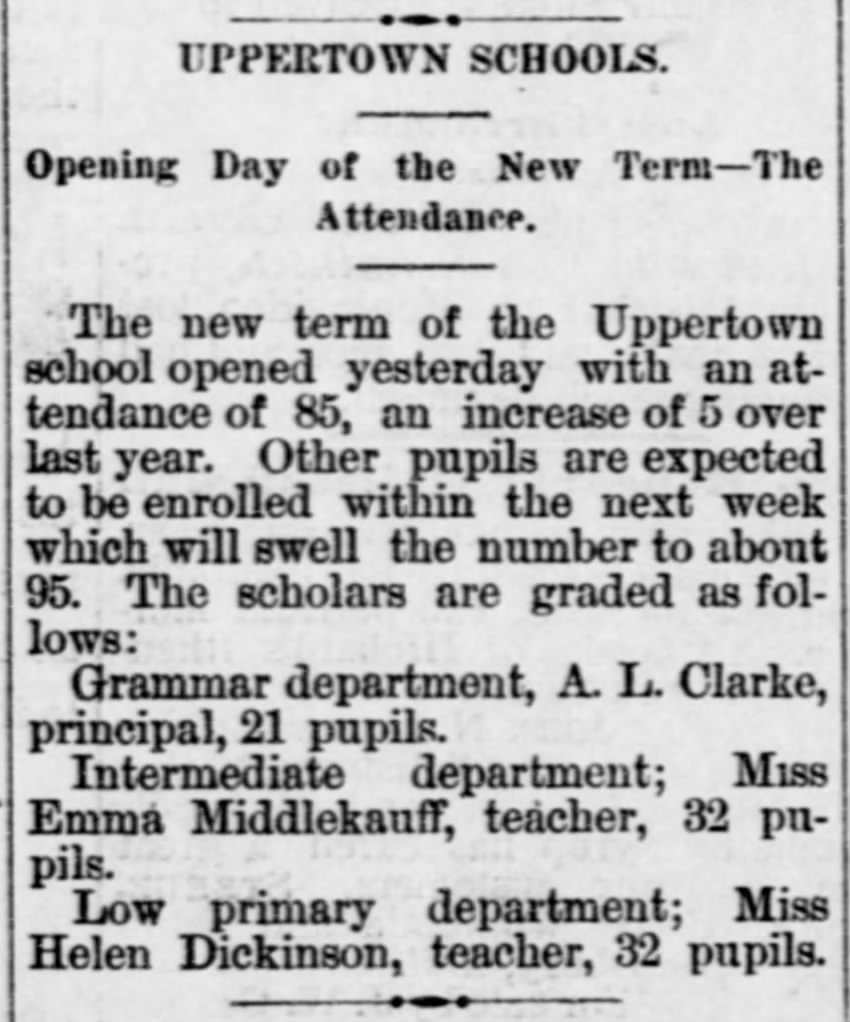

According to Sanborn fire insurance maps, this house was present at this location by 1888, although the exact date of construction is unknown. Helen Dickinson, daughter of deputy county clerk for Clatsop County, John P. Dickinson, lived in this home until her death in 1923. She was one of Astoria's most well respected teachers.

According to Sanborn fire insurance maps, this house was present at this location by 1888, although the exact date of construction is unknown. Helen Dickinson, daughter of deputy county clerk for Clatsop County, John P. Dickinson, lived in this home until her death in 1923. She was one of Astoria's most well respected teachers.

Across the street, you will now see the 4th site of our tour. 1337 Franklin Ave. was home to river pilot Captain Hiram Brown. Like many Astoria, this one was not actually built here. In 1852, this house was constructed one and a half miles away in Astoria’s Uppertown neighborhood, known at the time as Adairsville. Ten years later, Brown decided that he wanted to live in the more prestigious downtown. So how did a house get from one side of town to the other? The river of course. The house was barged down the Columbia and floated into the neighborhood at present day 10th and Franklin. Remember, most of Astoria was built over the tide flats. It wasn’t filled in and made more solid until after the 1922 fire. According to the National Park Service, promotional literature of the day called Astoria “Venice of the West.” Small boats could navigate underneath downtown and bob right up to the business. So, a house, such as this, could be barged near to its final resting place. Once at the edge of the backwater, the house was placed onto log rollers and maneuvered into this location. An addition was then added to it.

From the Letters of Charles Stevens:

“Astoria Dec. 8th 1862

Three years ago, Mr. Brown built him a house at the upper Town at a cost of about three thousand dollars, since that place has gone in, as the saying is, he and his partner moved their store down here over a year ago. His house stood some one hundred and fifty feet up a steep bank from the river. He wanted a house in the lower Town, but his lots are still higher than at the upper place. The man that built his house, proposed to move it. To bring it by land could not possibly be done as it is a thick forest, so they slid it down the bank to the water, then on two large scows, flotedit down here, landed it, hauled it up the bank, put in upon the lot, all without even cracking the plastering, and they are now living in it.”

“Astoria Dec. 8th 1862

Three years ago, Mr. Brown built him a house at the upper Town at a cost of about three thousand dollars, since that place has gone in, as the saying is, he and his partner moved their store down here over a year ago. His house stood some one hundred and fifty feet up a steep bank from the river. He wanted a house in the lower Town, but his lots are still higher than at the upper place. The man that built his house, proposed to move it. To bring it by land could not possibly be done as it is a thick forest, so they slid it down the bank to the water, then on two large scows, flotedit down here, landed it, hauled it up the bank, put in upon the lot, all without even cracking the plastering, and they are now living in it.”

1278 Franklin Ave.

This house was built sometime around 1896. It is a good example of a small single dwelling among other larger and more victorian-style homes in an affluent neighborhood. It was first owned by Emil Peterson, a fisherman working for Columbia River Packing Co. Over the years, there were several stewards to this home. In 1916, it was remodeled with craftsman bungalow-style features.

This house was built sometime around 1896. It is a good example of a small single dwelling among other larger and more victorian-style homes in an affluent neighborhood. It was first owned by Emil Peterson, a fisherman working for Columbia River Packing Co. Over the years, there were several stewards to this home. In 1916, it was remodeled with craftsman bungalow-style features.

1229 Franklin Ave. constructed in 1892

This house was occupied by John Quincy Adams Bowlby and his wife, Georgiana Brown Bowlby for over 30 years. They had three children, Violett, Roy, and Hugh. John Q A Bowlby was a busy man here in Astoria. Not only did he run a law practice, he served as county judge for several years. He was also president of of Astoria Savings Bank and the Astoria Chamber of Commerce, he owned many businesses, sat on a bunch of committees, and was a member of the local I.O.O.F lodge for over 50 years.

This house was occupied by John Quincy Adams Bowlby and his wife, Georgiana Brown Bowlby for over 30 years. They had three children, Violett, Roy, and Hugh. John Q A Bowlby was a busy man here in Astoria. Not only did he run a law practice, he served as county judge for several years. He was also president of of Astoria Savings Bank and the Astoria Chamber of Commerce, he owned many businesses, sat on a bunch of committees, and was a member of the local I.O.O.F lodge for over 50 years.

As we cross over 12th Street, you may have noticed that we never crossed a 13th street. Though the number 13 can often be shrouded by superstition, the missing 13th Street in Astoria is a little less legend worthy, but still interesting. In 1843, when John Shively and John McClure received their land claims, the street grid was designed to have a 13th St situated between 12th and 14th, however, each owner used different surveyors with disagreeing dimensions and the blocks did not align. So, in the end, 13th Street was skipped. You will find one block’s worth of 13th St. between Exchange and Duane, and will have an opportunity to see it later in this walk.

For a moment, turn around and compare this photo to what you see before you. This photo was taken on Franklin Ave. from 11th St. You'll notice that about half of the houses pictured are gone, but a few still remain standing. The third house on the left closest to 12th St. used to be a single family dwelling, then it became the YWCA. Today it is a pre-school. The preservation movement in Astoria has encouraged developers to adaptively re-use many homes and buildings as old as some of these instead of knocking them down and building brand new. You can also see that the original brick streets peek through the pavement on Franklin Ave. It is thought that streets at the turn of the 20th century were designed to be brick down the middle for horses and paved on the sides for automobiles. The piles of wood you see in the older picture were used for fireplaces inside the homes. Wood was delivered and dropped off in front of the houses. Pedestrians often found the piles cumbersome and in the way. If you continue on Franklin toward 10th St. we’ll see a few more old homes.

989 Franklin Ave. constructed in 1870

Supposedly, DeWitt Clinton Ireland lived in this house sometime between 1870s. Ireland was founder of many newspapers including The Astorian in 1873. He became mayor of Astoria in 1876 then was re-elected in 1880. He left Astoria in 1881.

Supposedly, DeWitt Clinton Ireland lived in this house sometime between 1870s. Ireland was founder of many newspapers including The Astorian in 1873. He became mayor of Astoria in 1876 then was re-elected in 1880. He left Astoria in 1881.

960 Franklin Ave.

The exact date of construction is unknown. It is known that the house appears in an 1879 photograph. Stylistically, it could date to the 1860’s.

The first owner of this house was John Fox. In the same year Fox moved into the home, he lost his wife, Francis Amelia Stewart Fox, in a tragic death due to tuberculosis leaving behind their two very young children, Grace and Chester. The children moved to Yamhill to live with family while John continued as President and Controlling Owner of Seattle-Astoria Iron Works. Fox never remarried. In 1893, Bar Pilot Captain Eric Johnson and his wife, Mary, roomed here with Fox and his son. Mary was daughter of steamboat captain H.B. Parker of Astoria and died in 1889.

The exact date of construction is unknown. It is known that the house appears in an 1879 photograph. Stylistically, it could date to the 1860’s.

The first owner of this house was John Fox. In the same year Fox moved into the home, he lost his wife, Francis Amelia Stewart Fox, in a tragic death due to tuberculosis leaving behind their two very young children, Grace and Chester. The children moved to Yamhill to live with family while John continued as President and Controlling Owner of Seattle-Astoria Iron Works. Fox never remarried. In 1893, Bar Pilot Captain Eric Johnson and his wife, Mary, roomed here with Fox and his son. Mary was daughter of steamboat captain H.B. Parker of Astoria and died in 1889.

These next two houses are going to give you another example of houses that have been moved. Moving houses in Astoria was more common than you would expect. Houses were moved across town, down the street, across the property, or sometimes simply shifted into a different direction. There are a number of reasons a house would be moved. In Captain Brown’s case, it was a matter of neighborhood preference. Other instances have been due to landslides.

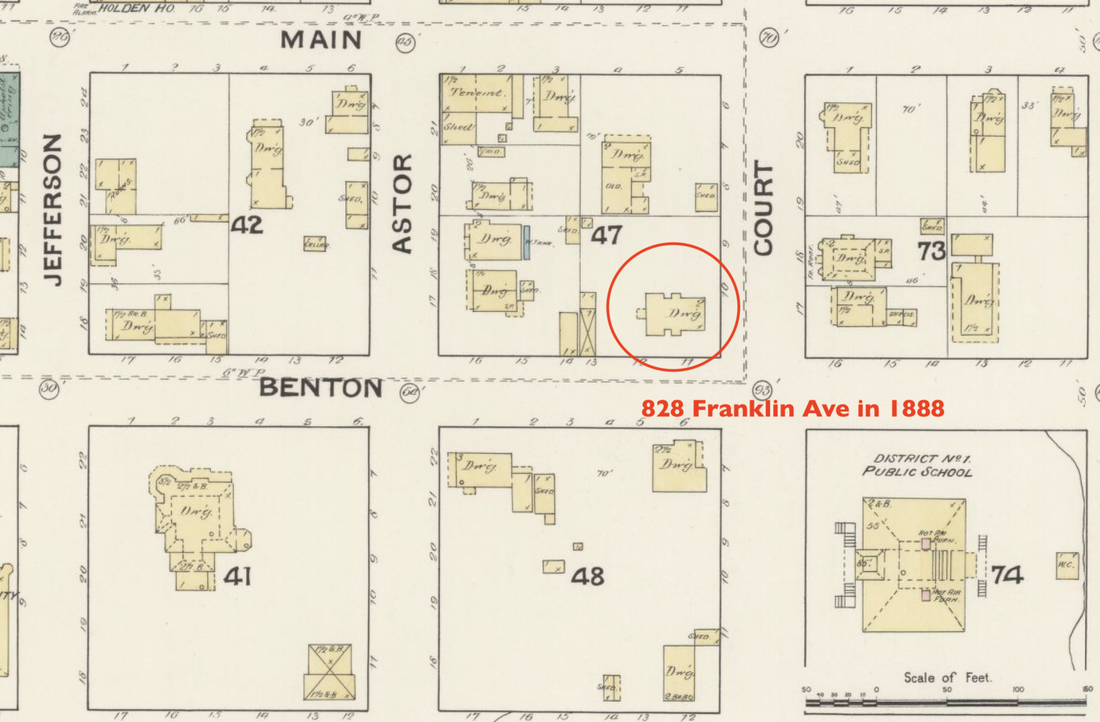

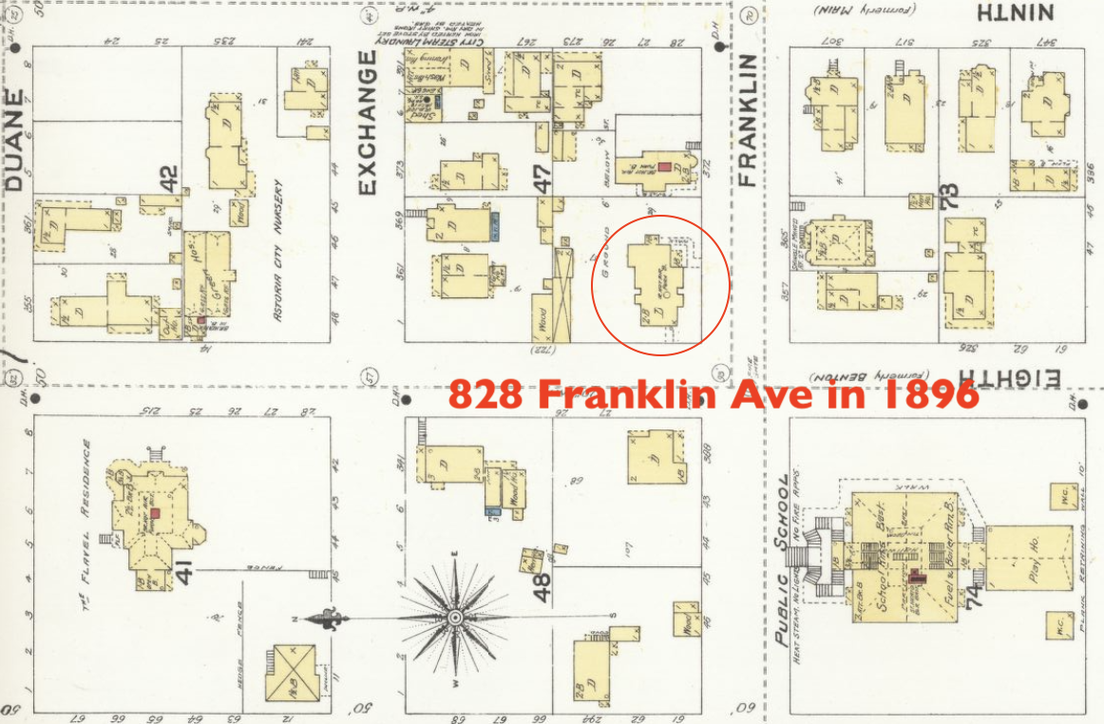

Sanborn fire insurance maps date back to 1867. They were used to assist fire insurance agents in determining the degree of hazard a residential , commercial, or industrial property would be to a fire. Today we use them to study the history and preservation of historical buildings. Sanborn maps are helpful to show historians and preservationists where houses have been moved from and to.

Sanborn fire insurance maps date back to 1867. They were used to assist fire insurance agents in determining the degree of hazard a residential , commercial, or industrial property would be to a fire. Today we use them to study the history and preservation of historical buildings. Sanborn maps are helpful to show historians and preservationists where houses have been moved from and to.

828 Franklin Ave. and 584 8th St. constructed in 1885

These two houses used to be a single home. It went through a series of moves since its initial construction. First the house was turned 90 degrees in 1896. You can see this change on the 1896 Sanborn map. Additionally, a large addition was built on its eastern side. Sometime between 1908 and 1920, one third of the eastern side and the addition were split off from the original building, moved west 30 feet, and made into separate rental quarters known as 828 Franklin Ave. The 584 8th St. portion had an eastern wing added.

The home had some prominent stewards over the years. It was originally built Conrad Boelling and designed to be a rental. Boelling came to Astoria early on and opened a hotel in 1848 when very little was established yet. His daughter, Mary Christiana Lydia Boelling married the well known Captain George Flavel. They lived in the 1880s mansion down the street on 8th St. between Duane and Exchange Streets. You can see the Flavel house on all three Sanborn maps marked with a 41. Before the house was split in half, Samuel Elmore was a renter in the home. Elmore was president of Elmore Cannery and helped organize the CRPA, the Columbia River Packers Association.

Let’s take a quick break from looking at houses, but try to stay in your 1800s shoes. Go to the corner of Franklin and 8th Streets and gaze down toward the river. All of these old houses have seen Astoria change tremendously since the 1800s. Today, you’ll see the Clatsop County Public Service Building up here on your right and Buoy Brewing down on the water. Try to imagine Astoria’s river line covered in wharves with warehouses and boarding houses.

At the foot of 8th Street in 1896, you would see Gray’s Dock on the right and H.B. Parker’s Dock and Warehouses on the left. These were both built north of where the riverwalk is now. Up a block, on Astor St. was a raunchy part of town known as Swilltown, which served as Astoria’s red light district. This area of town was where unknowing young men were supposedly ‘shanghaied’ through the floors of saloons or boarding houses and into boats underneath the wharves. The photo below was taken a few blocks Southeast of Swilltown at present day 10th and Marine Dr. This is the Occident hotel. A two story structure built on pilings over the tide flats. Notice in the background of the photo that the forests that once thrived in the hills of Astoria are all chopped down here.

A block up, things were a bit more serious. At 8th Street and Commercial was Astoria’s Post Office and Custom House which was completed in 1873. It was a rather monumental looking building made completely of stone. Unfortunately, its design was also its demise. Because it was not able to be heated, the stone structure grew to be extremely unsanitary and conditions were hazardous for the postal workers. It was replaced in 1933 with the post office you see today. Across the street from the post office was the first Clatsop County Court House. The original court house was not nearly as ornate as the 1904 brick building that stands today, instead it was a rather simple wooden construction. Behind it sat the second county jail which was built in 1882. That jail, while in the same location as the small jail, now Oregon Film Museum, is not the same building you see today. The old jail was was a larger structure with two turreted towers on either side of its entrance. The photograph below was taken at 2nd and Commercial Streets around the turn of the century. The post office is circled. You can see in this image that the entire river front was built much more than it is nowadays.

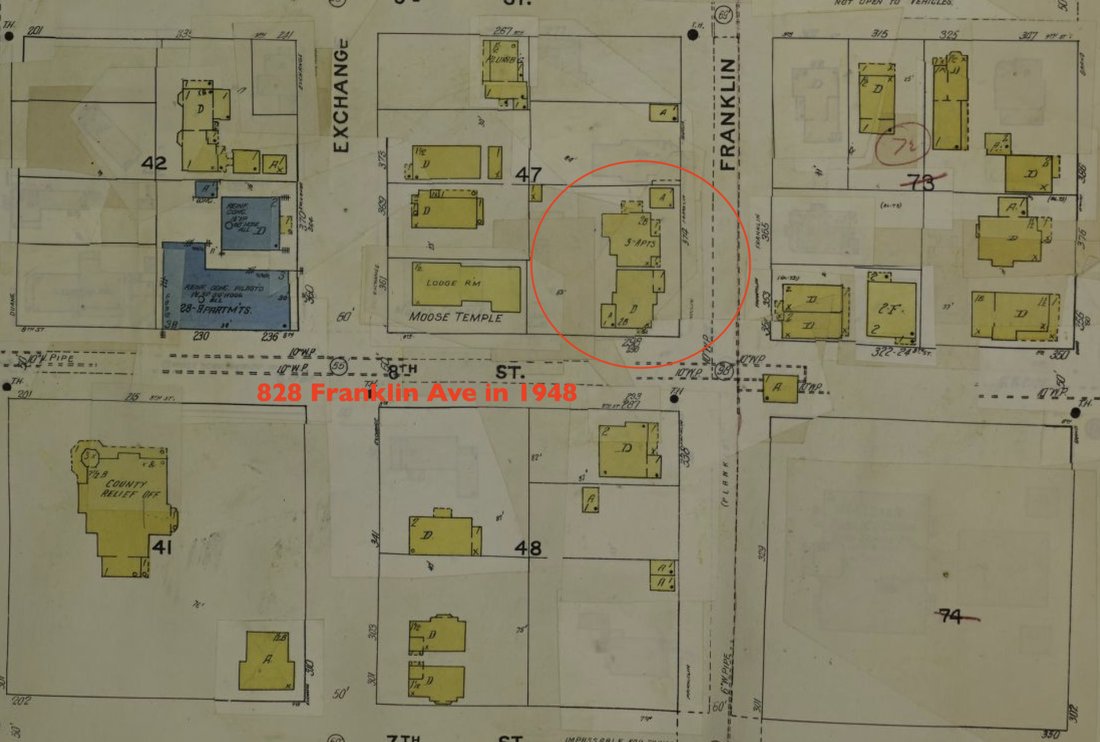

To your immediate left, you’d be standing near the steps of the McClure School. The 1882 three story building was where grades one through eight were taught. It was not until 1890, that Astoria served high school classes. At the top of the school building was the tower where the bell was housed. The sounds of 1800s Astoria were described as the ringing of bells. Whether from school or churches, there was often a bell clanging for public attention. McClure School was demolished in 1917. You can see the school on the 1888 and 1896 Sanborn maps, but its lot is vacant on the 1948 map.

The first public school of Astoria was over on 9th street between Exchange and Franklin. While the first Public School District was established in 1854, the school, itself wasn’t built until 1859. The simple one and a half story clapboard building utilized two rooms to teach the children. It later became a plumbing shop and educational services moved over to the McClure School.

All of these have long since been torn down and replaced. But thinking about them and imagining life back then sparks curiosity and keeps them woven into the fabric of history.

Let’s continue to take a look at a couple more houses that are still standing.

All of these have long since been torn down and replaced. But thinking about them and imagining life back then sparks curiosity and keeps them woven into the fabric of history.

Let’s continue to take a look at a couple more houses that are still standing.

788 Franklin Ave. constructed in 1884

Another rental owned by Conrad Boelling. An early steward to this home was one of Astoria’s first cannery operators, Marshall Kinney. His cannery operated at the foot of 6th St. and grew to be the city’s largest cannery during the 1880s.

Conrad Boelling, himself, lived at 765 Exchange St. in a house built in 1863. You can veer off to the left if you’d like to see it. Otherwise, continue on 8th and hang a right on Exchange St. On 8th between Exchange and Duane sits the grand 1885 Victorian Captain George Flavel house. This home is now a museum and you can explore its grounds and tour the inside of it. In the image below, you can see the Flavel House in the foreground, Conrad Boelling's square house in the middle, and the McClure School in the background.

Another rental owned by Conrad Boelling. An early steward to this home was one of Astoria’s first cannery operators, Marshall Kinney. His cannery operated at the foot of 6th St. and grew to be the city’s largest cannery during the 1880s.

Conrad Boelling, himself, lived at 765 Exchange St. in a house built in 1863. You can veer off to the left if you’d like to see it. Otherwise, continue on 8th and hang a right on Exchange St. On 8th between Exchange and Duane sits the grand 1885 Victorian Captain George Flavel house. This home is now a museum and you can explore its grounds and tour the inside of it. In the image below, you can see the Flavel House in the foreground, Conrad Boelling's square house in the middle, and the McClure School in the background.

817 Exchange St. constructed in 1860

Another example of moving houses. This building used to be much closer to its adjacent house, but was moved closer to 8th St. in 1900. You can see the difference if you look at the older Sanborn maps vs. the 1948 map. The house was built by Job Ross and he lived in it until 1896. Ross was the manager of the pre 1922 fire Liberty Theatre, which at that time was located at 7th and Bond Streets. This home has operated as many different things over the years including a duplex, a Moose Lodge, a Mormon church, and a pottery studio. You can still see the Moose Lodge sign on the front facade of the building.

Another example of moving houses. This building used to be much closer to its adjacent house, but was moved closer to 8th St. in 1900. You can see the difference if you look at the older Sanborn maps vs. the 1948 map. The house was built by Job Ross and he lived in it until 1896. Ross was the manager of the pre 1922 fire Liberty Theatre, which at that time was located at 7th and Bond Streets. This home has operated as many different things over the years including a duplex, a Moose Lodge, a Mormon church, and a pottery studio. You can still see the Moose Lodge sign on the front facade of the building.

You’re going to continue on Exchange for a handful of blocks until you reach 14th. In the mean time, I’ll tell a bit more about Astoria and its 1800s history.

Before Astoria and its surrounding areas were industrialized, this land was completely covered in evergreen trees. The river separated the Chinook-occupied land of the north, while the southern shore was where the Clatsop tribes lived. After explorers arrived from all different directions, several acres of those trees were cut down, milled, and used to construct roads and buildings.

In the mid 1800s, the West promised gold and donated land claims. People came from far and wide to lay their roots and find financial opportunities here.

Astoria began to find prosperity in the timber industry. Mills were built along the north and south sides of the river and provided wood to the community at much lower prices than San Francisco timber. Mills created jobs and brought people back up north from their failure to make themselves rich off California gold. Timber hasn’t stopped providing this area with its natural resource economy, but what Astoria and the Columbia River is really known for is salmon.

You can’t talk about Astoria in the 1800s without mentioning the canneries. Being at the mouth of the Columbia River, Astoria had a geographical advantage to catching salmon and was able to turn it into a whole economy. Astoria’s first cannery opened in 1874. This growing industry inspired individuals from all over the world to journey to Astoria for work and a fresh start on life. In 1885, The Morning Astorian published a description of Astoria by a visitor from San Fransisco which reads “Astoria contains the most polygon collection of humanity on the American continent.” It goes on to describe Astoria residents as natives of the Scandinavian peninsula, Finns, Russians, Italians, Greeks, and Sicilians.

In the mid 1800s, the West promised gold and donated land claims. People came from far and wide to lay their roots and find financial opportunities here.

Astoria began to find prosperity in the timber industry. Mills were built along the north and south sides of the river and provided wood to the community at much lower prices than San Francisco timber. Mills created jobs and brought people back up north from their failure to make themselves rich off California gold. Timber hasn’t stopped providing this area with its natural resource economy, but what Astoria and the Columbia River is really known for is salmon.

You can’t talk about Astoria in the 1800s without mentioning the canneries. Being at the mouth of the Columbia River, Astoria had a geographical advantage to catching salmon and was able to turn it into a whole economy. Astoria’s first cannery opened in 1874. This growing industry inspired individuals from all over the world to journey to Astoria for work and a fresh start on life. In 1885, The Morning Astorian published a description of Astoria by a visitor from San Fransisco which reads “Astoria contains the most polygon collection of humanity on the American continent.” It goes on to describe Astoria residents as natives of the Scandinavian peninsula, Finns, Russians, Italians, Greeks, and Sicilians.

The cannery industry grew through the 1880s and with it, encouraged a proportional growth of the Chinese population. Many individuals emigrated from China to Astoria to work in these canneries, most of them finding residency in bunkhouses just behind the cannery buildings. The riverfront was lined with these canneries and heavily sprinkled with bunk and boarding houses for the workers. At that time, the majority of the labor in the canneries were Chinese. According to the U.S. census, Astoria had a population of 7,055. 2,045 of them were Chinese. That is almost a third of the population. In the 1880s, Astoria had its own small Chinatown with a Chinese theater and Chinese school. The Chinese population dramatically declined after the 1882 signing of the Chinese Exclusion Act. Additionally, competition and mergers within the fish industry caused more competition in labor as well as the invention of butchering machines which replaced the reliance on human labor. Women began to dominate cannery work at the end of the 19th century.

The 1870s saw the fishing industry dominated by the Finnish. Many Finns came to the U.S. for a better life. The 1860s was a tumultuous time for farming in Finland causing starvation and giving people few options other than to leave. Astoria, itself, mimicked much of the weather and terrain of the Northern parts of Europe making it an inviting and nostalgic place to call home. The 1880 U.S. census counted 203 Finns living in Clatsop County. That number grew as the fish industry found its footing in Astoria and word spread that there were jobs here. Many of the Finnish men arrived in Astoria with tons of fishing experience making it easy to fit into the Pacific Northwest industry. Like the Chinese, many of the Finns lived in bunk and boarding houses behind the canneries to whom they were employed. The neighborhood under the bridge and surrounding areas, known as Uniontown named after Union Cannery, became home to a large Finnish population as a place to live and open businesses.

From New Land, New Lives: Scandinavian Immigrants to the Pacific Northwest by Janet E. Rasmussen:

“There were many boardinghouses in Astoria because many single men came here. Father was eating in a boardinghouse and he had a room with this family near the boardinghouse. That part of Astoria is Finnish Town, Uniontown.”

Hilma Salvon, a Finnish immigrant

“I like it, but this is so small since New York. People wonder how girls leave New York and come to Astoria because it’s so small. But after, I get used to it. I find that boy. We go together two years before we married. Astoria the whole time. I like here. I got my family here."

Hanna Sippala, a Finnish immigrant

“There were many boardinghouses in Astoria because many single men came here. Father was eating in a boardinghouse and he had a room with this family near the boardinghouse. That part of Astoria is Finnish Town, Uniontown.”

Hilma Salvon, a Finnish immigrant

“I like it, but this is so small since New York. People wonder how girls leave New York and come to Astoria because it’s so small. But after, I get used to it. I find that boy. We go together two years before we married. Astoria the whole time. I like here. I got my family here."

Hanna Sippala, a Finnish immigrant

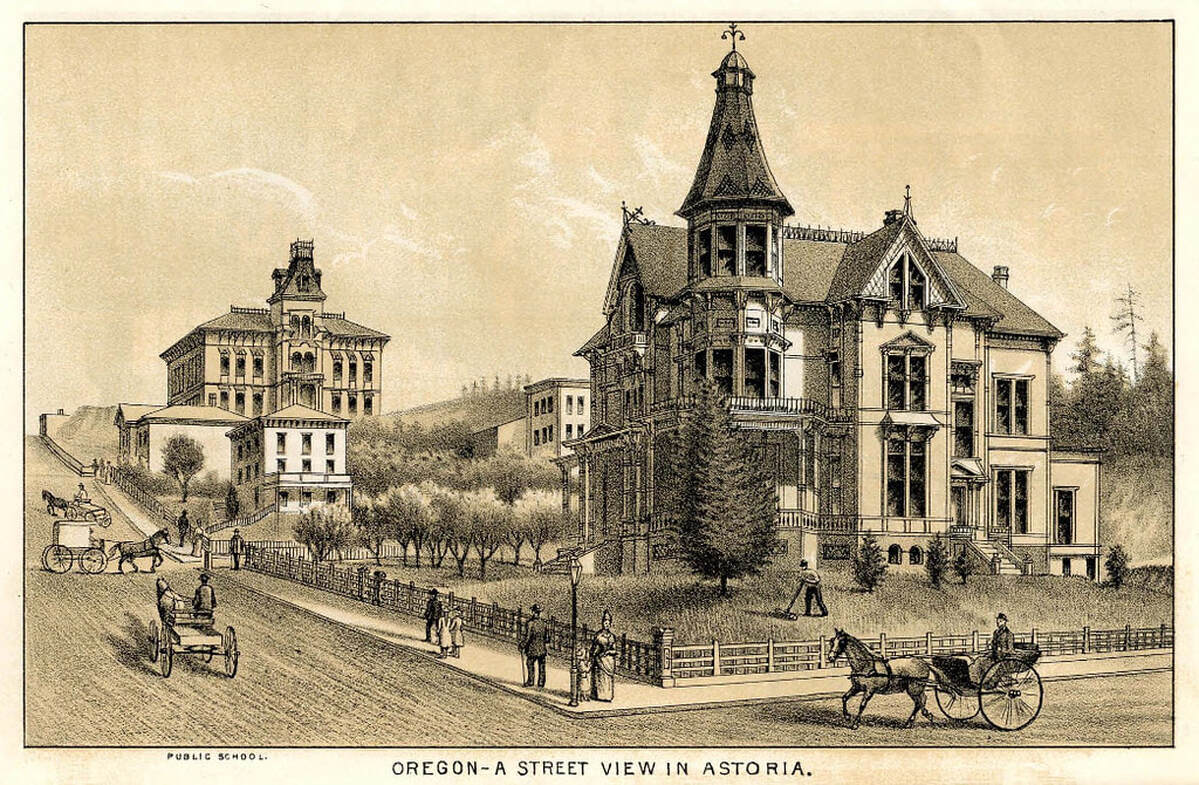

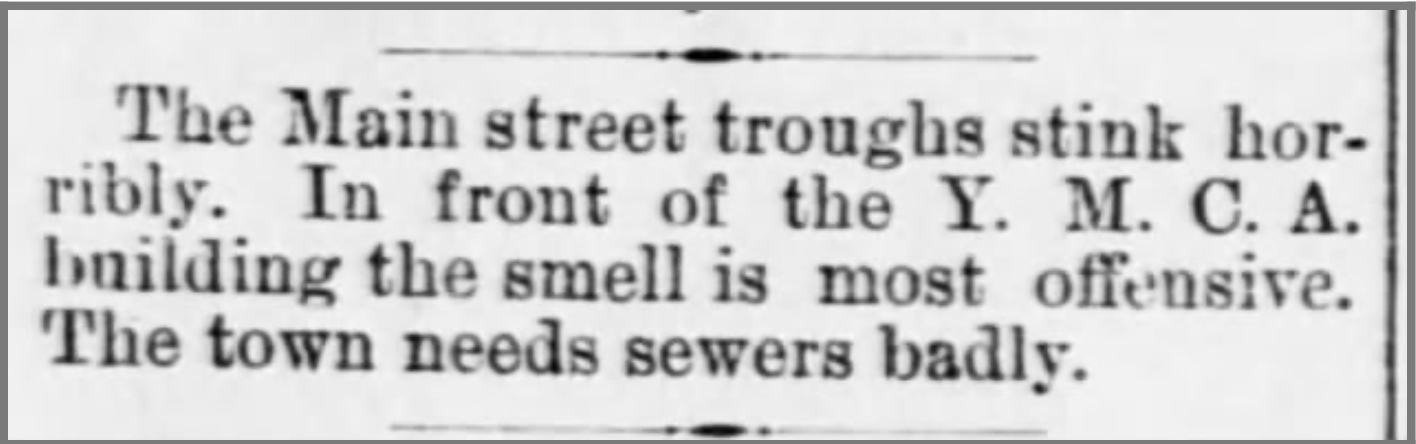

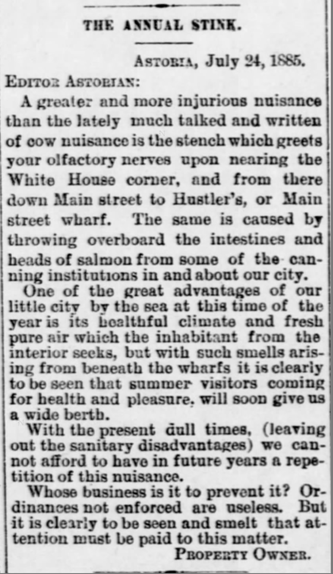

While the fish industry brought in a bunch of money to Astoria, it also brought something not so desired: stink

Processing fish can be odiferous work. Even today, you can catch a strong whiff if you’re on the West side of town at the right time. In the 1800s, a lot of waste from canneries or fish oil factories was dumped straight down into the water beneath the building, but when the tide was low, rotting fish bits would remain behind leaving a strong odor.

Processing fish can be odiferous work. Even today, you can catch a strong whiff if you’re on the West side of town at the right time. In the 1800s, a lot of waste from canneries or fish oil factories was dumped straight down into the water beneath the building, but when the tide was low, rotting fish bits would remain behind leaving a strong odor.

The Annual Stink

Astoria, July 24, 1885

Editor Astorian,

A greater and more injurious nuisance than the lately much talked and written of cow nuisance is the stench which greets your olfactory nerves upon nearing the White House corner, and from there down Main Street to Hustler's, or Main Street wharf. The same is caused by throwing overboard the intestines and heads of salmon from some of the canning institutions in and about our city.

One of the great advantages of our little city by the sea at this time of the year is its healthful climate and fresh pure air which the inhabitant from the interior seeks, but with such smells arising from beneath the wharfs it is clearly to be seen that summer visitors coming for health and pleasure, will soon give us a wide berth.

With the present dull times, (leaving out the sanitary disadvantages) we cannot afford to have in future years a repetition of this nuisance.

Whose business is it to prevent it? Ordinances not enforced are useless. But it is clearly to be seen and smelt that attention must be paid to this matter.

Property Owner

Astoria, July 24, 1885

Editor Astorian,

A greater and more injurious nuisance than the lately much talked and written of cow nuisance is the stench which greets your olfactory nerves upon nearing the White House corner, and from there down Main Street to Hustler's, or Main Street wharf. The same is caused by throwing overboard the intestines and heads of salmon from some of the canning institutions in and about our city.

One of the great advantages of our little city by the sea at this time of the year is its healthful climate and fresh pure air which the inhabitant from the interior seeks, but with such smells arising from beneath the wharfs it is clearly to be seen that summer visitors coming for health and pleasure, will soon give us a wide berth.

With the present dull times, (leaving out the sanitary disadvantages) we cannot afford to have in future years a repetition of this nuisance.

Whose business is it to prevent it? Ordinances not enforced are useless. But it is clearly to be seen and smelt that attention must be paid to this matter.

Property Owner

“J.L. Bellimer, foreman of the warehouse, said: ‘On many days of late the stench has been almost unbearable and in the last two weeks three hands have been made so sick as to vomit.” Miss Annie Peterson said: “The smell is so bad that some days I cannot eat my dinner and I get the headache so I cannot run my machine as fast as when I am well.’ Chas. Hough, a machinist said: ‘The foul smell from the oil works is very obnoxious and frequently turns my stomach. Often I can’t eat my dinner and am not able to work as I should.’”

-The Morning Astorian 27 May 1899

-The Morning Astorian 27 May 1899

In addition to the fish odor was the smell of sewage. Before proper piping was installed, much of Astoria’s sewage flowed into the river beneath the houses.

On a lighter, less stinky note, the late 1800s is when Astoria established its railway and began seeing more travel in and out of the city. In 1898, the Astoria & Columbia River Railroad line was completed. The train serviced tourism to and from Portland, especially those escaping summer heat of the Willamette valley, but it also went down to Seaside, giving way for travelers to have an easy route to the Pacific Ocean. the A&CR was also used for the timber industry to ship lumber between the Oregon Coast and Columbia County. About a hundred years later, the line went out of service. Today the track is used to run Astoria's Old 300 trolley.

As you make your way down Exchange, you will pass Astoria’s one block stretch of 13th Street. 13th Street extends as an alley between two downtown buildings as a quick connection between Duane and Commercial Streets. In 2019, a mural was painted by local artist Andie Sterling using native elements as the color palette. Turn left on 14th and you’ll see the Norblad Hotel. This hotel did not exist in the 1800s. In fact, it was built just after the great 1922 fire. In 1861, this was where you would have seen the Clatsop Mill. Originally known as Dad’s Mill or the Astoria Steam Sawmill, the mill had a log boom that reached all the way from the Y.M.C.A to where the Liberty Theatre is today! Imagine a mill in the middle of downtown Astoria today. It would seem really dangerous and out of place. This location appropriately served the Clatsop mill due to the fact that it was built over the water.

On July 2nd at about 6 pm, the fire bell rang signaling a fire at Clatsop Mill. At that time, the fire tower stood behind the fire station located beside City Hall at 11th and Commercial Streets. The fire crawled down Commercial St. burning down everything in its path on both sides of the streets between 14th and 17th. Even the sidewalk was destroyed since it, like the building was constructed with wood. While this fire was not as huge as the 1922 fire, Astoria still lost stores, saloons, a hotel, and the O.R. & N. Dock where the fire ended.

According to Sanborn maps from 1884 through 1908, it appears that this area remained as open tide flats without intention to rebuild anything there. The area probably reminisced the water front along the river and Young’s bay where pilings stand empty out of the water’s edge. The Norblad was built here during the secondary period just after the 1922 fire. The original owner of the mill, Ferdinand “Dad” Ferrell lived in the house on the corner of 14th and Exchange Streets where it continues to stand today. His house was built around 1860 and survived both the 1883 and 1922 fires. It was converted into apartments in 1896. The photo above was taken at the time of the fire. Notice in the image that the streets were built with wood. If you look in the center of the photo, you can also see how the downtown was built over the water and the buildings stood atop piers. The majority of these buildings are gone with history. Odd Fellows is marked in the picture to give you an idea of where present day downtown stood in conjunction to the Clatsop Mill fire.

This panorama was taken at the turn of the 20th Century. Astoria came a long way since the Tonquin arrived and set up their post. It has come a long way since this photograph was taken as well.

If you take a left onto Duane St., you can head back to the Lower Columbia Preservation Society office for any questions or comments regarding this tour.

If you take a left onto Duane St., you can head back to the Lower Columbia Preservation Society office for any questions or comments regarding this tour.